One of the challenges that many new climbers face is lacking grip strength to sustain climbing holds. Climbing grips like crimps, pinches, pockets, friction holds and open-hand grips require vice like strength to be sustained through a move. Without proper hand strength, the hand and fingers tend to open up and fail.

The fundamentals of developing grip strength for rock climbers involve: first, conditioning the tendons and ligaments to safely endure heavier loads, and second, building muscle via incremental muscle progression exercises.

Grip Strength Is Not Just About Building Muscle

Usually, a conversation about strength enhancement is focused on muscle development. However, when it comes to grip strength enhancement for rock climbing, there are actually two fundamental components considerred for development: muscles and tendons.

Traditionally, grip strength training workouts combine muscle growth and tendon development in workout routines performed a couple times a week. Muscles are strengthened through high intensity loading and require two to three days of recovery between loading sessions.

Tendon and Ligament Development: Often Overlooked by Rock Climbers

The problem for many new and intermediate climbers is that muscle capacity exceeds the capacity of the tendons and ligaments to sustain the same loads that the muscles are capable of bearing.

Tendon tissues connect muscle to bone. Ligament tissues connect bone to bone. When tendons and ligaments do not have the same maximum load capacities as the muscle, they are considered to be underdeveloped. Underdevoloped tissues can be prone to injury and take a long time to heal.

Climbing involves many opportunities to overcommit–it’s kind of part of the sport–to see how far you can go–or find out what you can’t do. It is natural for new climbers to want to climb beyond their real capacity. Although muscle capacity may be advanced, tendon and ligament strength may be underdeveloped.

In summary, climbing holds—such as the crimp, can tend to open up because of underdevloped tendon and ligament tissues and the climber must exert excessive muscle effort to maintain a grip on the hold subjecting the tendons and ligaments to the risk of overexertion and injury.

Ignoring Underdeveloped Ligaments Can Lead to Injury

It goes without saying, most climbing injuries are associated with a tear or pull of a ligament or tendon tissue because it is difficult for climbers to recognize when muscle exertion exceeds the healthy capacity of tendon and ligament tension. The only thing worse than not being able to finish a climbing route is not being able to climb.

New climbers are generally discouraged from engaging in strenuous grip strength training exercises due to the high risks of injury—straining or tearing tendon and ligament tissues. Many trainers will not recommend high tension exercises to new and intermediate climbers such as those associated with the hang board because of the high propensity to injury.

Needless to say, for new and intermediate climbers, because the tension capacity of tendons and ligaments is not parallel with muscle load capacity, traditional methods that combine the two fundamentals of grip strength training in workout sessions two times a week lead to slow and unsatisfying climbing progression.

What is the Secret to Quickly Build Grip Strength for Rock Climbers?

Here’s the rub, modern research shows1 that tendons and ligaments obtain maximum response after just 10 minutes of loading and only require 6 hours or so of recovery between stimulous. Therefore, stretch and tension exercises for tendons and ligaments can be facilitated through 10 minute training sessions that can be repeated 2 or 3 times per day—easily accommodated into even the busiest of schedules.

Tendons, finger pulleys and ligaments can be strengthened. Where muscle growth involves exercises that expand and contract, tendons and ligaments are strengthened through resistance exercises and stretching. Additionally, where muscle fibers require two or more days to repair after just a few sets of moderate exercise, tendons and ligaments can fully recover in just six hours2.

Seperating Muscle Training and Tendon Conditioning Accelerates Grip Strength Enhancement

This is fantastic news for climbers! In essence, grip strength development can and should be divided into two programs. One program can emphasize muscle growth—which for new and intermediate climbers may simply involve climbing sessions at the rock gym or crag two times a week. And another program can be performed at a much lower intensity level to emphasize the development of healthy tendon and ligament tissue—two or three times a day in brief 10 minute sessions.

Since the tendons and ligaments for new and intermediate climbers will likely have a much lower capacity for maximum exertion than the muscles, initial training and conditioning for tendons and ligaments should be performed at lower intensity levels.

Separating the workouts allows the climber to simultaneously build strength and expedite the development of healthy tendon and ligament tissue facilitating more rapid grip strength development and overall climbing progression while minimizing injury risk.

Here is the Secret for Building Rapid Grip Strength For Rock Climbing

In essence, the best way for new climbers to quickly build grip strength is by implimenting two separate work out routines. One routine should empasize muscle and stamina growth and may require 2-3 days rest between sessions. The other routine should incorporate frequent low tension stretches that focus on conditioning the tendons and ligaments in the fingers, hands, forearms, and shoulders. These sessions should be no longer than 10-15 minutes and can be performed multiple times per day. The key to these sessions is frequency and avoiding over exertion.

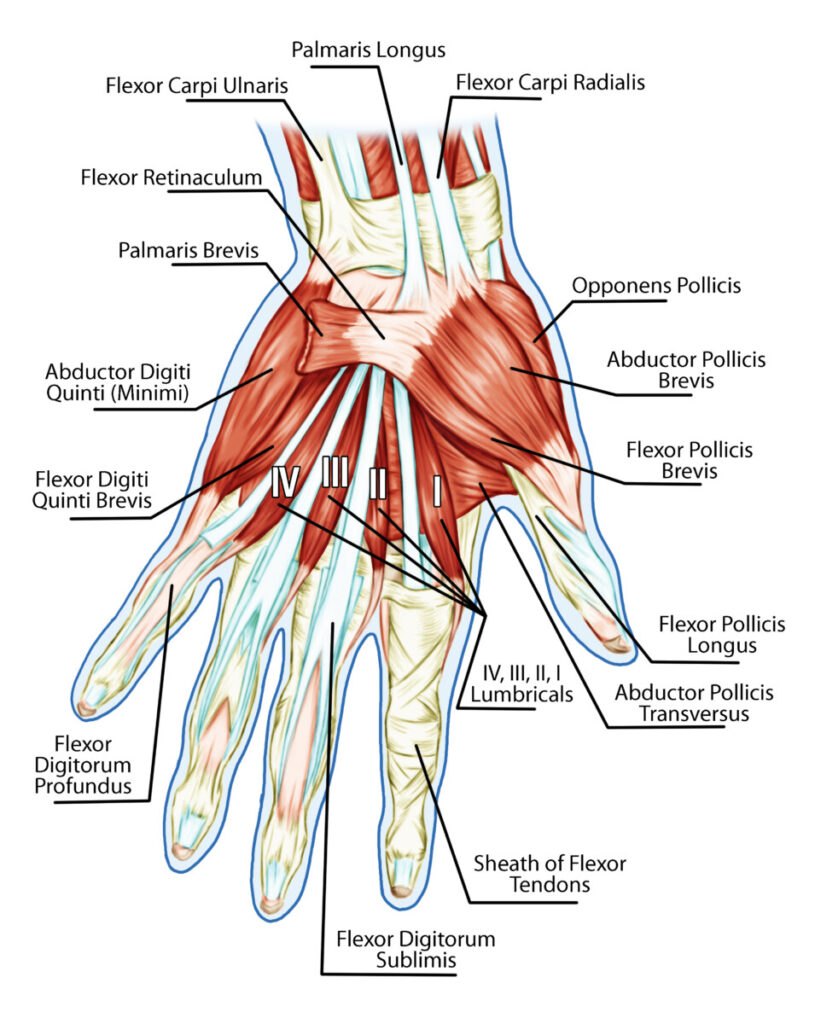

It is important to take a step back and reflect that the hands are a biomechanical machine densely composed of ligaments, tendons, pulleys, and muscles. Our hands still have a similar structure as when we were swinging through the trees just a few million years ago. Therefore, it goes without saying, our hands and fingers still have the ability to gain incredible strength.

When the tendons and ligaments are stretched and strengthened through an active frequent separate training program, a climber will notice that grips and holds become vice-like and easier to sustain after just a few weeks. Focusing on hand and grip strength enhancement can greatly improve the climbing experience for both novice and experienced climbers. Not only will it speed up progression by allowing the climber to stay on the wall longer it will also help to prevent injury.

Do Not Omit Whole Body Strength Training

Overall, strength training is great and shouldn’t be underestimated or overlooked. Many climbers and coaches will tell you that the key to climbing is in the legs. This may be true and definitely shouldn’t be overlooked. However, while whole body exercises have tremendous significance in the overall development of the climber, building early endurance strength in the hands and fingers will greatly speed up climbing progression and help prevent injury. Enhancing grip strength early on facilitates more efficient use of time training and a greater sense of accomplishment.

Which Climbing Grips to Emphasize During Strength Training?

A new climber will find many different types of holds at the crag or rock gym such as: jugs, mini jugs, edges, slopers, pinches, pockets, underclings, cracks, horns, volumes and gastons. While there are several types of strength training exercises that help strengthen the muscles and tendons used for gripping onto these various hold types, most of them incorporate some basic component or variance of the crimp.

The Crimp

The crimp grip lends itself to be the perfect grip for strengthening the tendons and ligaments.

There are three types of crimp: open, half, and closed. The only two recommended for beginner climber workouts are the open and half crimps. Excessive training with the closed crimp can lead to injury.

Open Crimp

The Open Crimp involves gripping a climbing edge with just the fingertips. The rest of the hand and fingers are extended and stretched across as much surface area of the hold as possible to create additional friction. For beginner and intermediate climbers, the open crimp is extremely difficult. The muscles and tendons at or near the fingertips are typically underdeveloped. However, once the fingers have been strengthened, climbers can take greater advantage of this grip as its implementation can reduce fatigue and help prevent injury.

Half Crimp

The Half Crimp involves gripping an edge with the fingers bent at or near a 90 degree angle. It is one of the most commonly used grips in climbing. For beginner climbers, it isn’t quite as challenging as the open crimp, but again, with the hand and finger muscles and tendons being highly underdeveloped, over usage of the half crimp can lead to injury. That being said, with proper training and exercise, being able to effectively implement the half-crimp into a climbing routine can greatly help a climber excel their climbing capabilities.

Full Crimp

The Full Crimp technique is the same as the half crimp except the thumb is wrapped over the forefinger to essentially lock the crimp. Overuse of the full crimp, especially by novice climbers, can quickly lead to injury. If the finger muscles are not strong enough to hold a half crimp, forcing the hold with the thumb puts undue strain on tendons and ligaments that haven’t been adequately strengthened to sustain such holds.

Typically, training programs do not recommend exercises that incorporate the full crimp due to the potential injury factor.

Exercise Programs—Avoid Maximum Exertion

Creating healthy tendon and ligament tissue through a training program should be approached with caution. Remember, it is likely that the tendons and ligaments are underdeveloped. They need to be able to sustain progressively heavier loads without sustaining injury. However, determining a starting point and deciphering how much is too much can be difficult to assess.

What is the Best Method to Strengthen Tendons and Ligaments?

The Hangboard

Meet the hangboard. The hangboard can be a very useful piece of training equipment. It’s affordable and can be manufactured or engineered to be mounted above most any door frame. It offers a variety of different slopers, edges and pockets of different depths all in one place. It becomes an extremely useful tool for the trainee to be able to find appropriate holds to start their training and offers additional holds that can be used for progression.

There are a lot of different types of hangboards available in the market. They are cheap, easy to install, and some or even portable. Here are a few examples:

The hangboard becomes particularly useful when developing and establishing an exercise routine. In an initial assessment, a climber should find and record their maximum hang capabilities on 3-5 various holds and use this as a gauge for progress improvement.

Record Maximum Hangs

Record maximum hangs on edge or pocket holds that can be sustained for 10-12 seconds and holds that can be sustained for 1-2 seconds or less. New climbers should avoid weighted hangs where additional weights are used.

Establish a “No-Hang” Routine

Once maximums have been recorded the hangboard can then be used to perform stretch and tension exercises that do not require maximum loading or free hanging. In fact, the feet should never leave the ground for these exercises. It’s called the “no-hang” and may look strange for those unaccustomed to this technique. For some, a chair or stool can be used to give the trainee additional height if needed. New and intermediate climbers should avoid exercises that involve more than 80% of their body weight. New climbers may want to start around 60%. Starting lower is better and will help prevent injury.

It is helpful when initiating the exercises to use a scale to determine what it feels like to hang at 60-80%.

Select multiple grips to use for your routine. This needs to incorporate grips that can be easily sustained with 60-80% body weight for 10-12 seconds and may incorporate variations of: four finger half crimps, three finger half crimps, two finger open crimps, etc. Rest after each rep for around 50 seconds. The key is that all of the fingers are being stretched and strained for a period of 10 minutes. The total workout includes just 10 reps and does not need to be longer than 10 minutes.

Allow 6 hours rest between workouts.

Repeat.

Repeat “No-Hang” Routine 3 Times a Day for 4-6 Weeks

The workout can be completed up to 3 times per day and the overall routine can be repeated daily.

Do not be tempted to measure maximum hang capabilities frequently. Frequent max hangs lead to injury—especially for new and intermediate climbers. It is okay to gradually increase your load but do not exceed 80%. Just stick to the program for 4-6 weeks.

Assess Maximum Hang Progression

After 4-6 weeks, test maximum hang progression.

Make Progressive Adjustments to Hangboard Routine.

Repeat.

Example Hangboard Routines

Here are examples of routines that can be used2:

Routine 1—performed 2-3 times daily for 4-6 weeks:

- 3 reps of the four finger half crimp on an edge 70% increased to 80% over time.

- 3 reps of a three finger half crimp on an edge 70% increased to 80% over time.

- 2 reps of varying two finger open crimps in a pocket 60% increased to 70% over time.

- 2 reps of varying two finger half crimps on an edge 60% increased to 70% over time.

Routine 2—performed 2-3 times daily for 4-6 weeks:

- 2 reps on a sloper 80%.

- 3 reps four finger half crimp on an edge 70% increased to 80% over time.

- 1 rep three finger half crimp on an edge 70% increased to 80% over time.

- 4 reps varying two finger open crimps in a pocket 60% increased to 70% over time.

Learn How to Avoid Getting Pumped

Once tendon and ligament tissues have been strengthed, a climber will be able to reduce the risk of injury while spending more time on the wall. Simultaneously learning how to stave off the climbing pump can also greatly help the progression of the climber. See my article: How to Avoid Getting Pumped While Rock Climbing for methods and tips that will help in this regard.

Resources:

1“Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review“; Scandinavian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sports; Dustin J. Oranchuk, Adam G. Storey, André R. Nelson, John B. Cronin

2The “Simplest” Finger Training Program with Dr. Tyler Nelson